[Paper Reading] GPUPool: A Holistic Approach to Fine-Grained GPU Sharing in the Cloud (PACT'22)

This blog is a write-up of the paper “GPUPool: A Holistic Approach to Fine-Grained GPU Sharing in the Cloud“ from PACT’22.

Motivation

This paper focuses on the GPU sharing in cloud scenarios.

Currently, existing GPU sharing techniques can be categorized into 2 types:

Time-sharing means executing each concurrent VM on a full device in a round-robin fashion. Pros: Simple and mature. Cons: VMs could still under-utilize the hardware within each time slice.

Shape-sharing: split a device into partitions and allows multiple workloads to execute on different partitions simultaneously.

Space-sharing can be categorized into 2 types:

Coarse-grained assigns disjoint sets of streaming multiprocessors (SMs) and memory channels to concurrent workloads. For example, Nvidia MIG. Pros: offers great performance isolation among tenants of the same GPU. Cons: (i) resource under-utilization within each SM consisting of heterogeneous functional units (e.g., FP32, INT, FP64, Tensor Cores) meant for different workload types. (ii) inefficient memory bandwidth usage caused by the bursty nature of GPU memory traffic.

Fine-grained allows different workloads to co-run on the same SMs and request memory bandwidth flexibly, such as CUDA Stream and MPS. Pros: Better hardware utilization.

The key problem of GPU sharing in data center is performance unpredictability. It contains 2 key challenges:

Mitigating interference. The amount of performance improvement from fine-grained sharing varies drastically depending on how compatible the concurrent workloads are in terms of resource usage. Also, the interference cannot be statically estimated. So, it is non-trivial to determine compatibility among a large number of incoming jobs in the cluster.

Providing QoS guarantees.

Existing solutions:

Software-based: kernel slicing or a persistent thread model. Cons: high scheduling overhead.

Hardware-based: integrate sophisticated resource management logic into hardware to allocate resources for concurrent kernels. Cons: expensive and also inflexible.

Common problems of existing solutions:

They do not concern with interference mitigation at the cluster level.

They do not handle scenarios where incoming jobs must be distributed among multiple GPUs to satisfy QoS constraints.

Problems of hardware TB scheduler which hinder the fine-grained sharing:

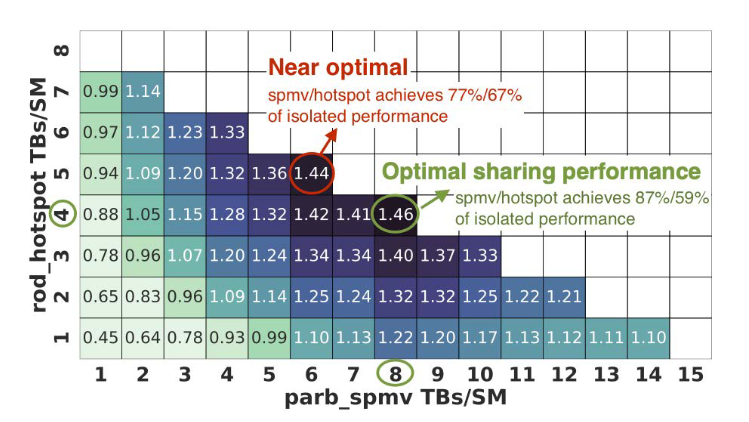

It always attempts to launch as many thread blocks per SM (TBs/SM) for each kernel as allowed by the execution context storage constraints (e.g., registers, shared memory, thread slots). It leaves insufficient resources for concurrent kernels. As showed in Figure 1, if we can individually set the TBs/SM for each kernel, we may achieve a higher throughput.

It only dispatches concurrent kernels onto SMs after the earlier arriving one completes launching all the thread blocks specified by the kernel grid size. This will force an almost serially execution of kernels in some scenarios.

GPU applications in the cloud fall into two main categories: latency-sensitive, and throughput-oriented. Throughput-oriented workloads are good candidates for hardware space-sharing. They have the following characteristics:

Most workloads involve a large variety of kernels with different hardware resource utilization characteristics (e.g., CNN: compute-intensive, batch-norm: memory-intensive).

Active SMs are underutilized in some resources (FP, tensor core, memory bandwidth).

They typically repeatedly execute the same sequence of kernels (e.g., ML).

Relaxed QoS Requirements.

Design

This paper proposed a hardware-software co-designed strategy to solve these challenges.

Hardware

This paper changes the default behavior of CUDA runtime to make it more suitable for fine-grained sharing:

Allows CUDA runtime to program the TBs/SM setting as one of the kernel launch parameters. The value of TBs/SM is selected by the performance predictor.

Make the TB scheduler launch TBs from any concurrent kernels whenever they are running under their TBs/SM quota.

Software

Concept Explanation:

- Job: a task submitted by user, such as a DNN training task. It may be iterative and contains multiple kernels.

- Kernel: CUDA kernel.

- Normalized Progress (NP): $t _ {isolate} / t _ {co-execute}$.

Two key observations:

Co-execution performance of GPU kernels is highly correlated with resource utilization of individual kernels measured when running in isolation.

Once we have predicted which job pairs can co-execute without violating QoS requirements, the scheduling task can be reduced to the classic maximum cardinality matching problem in graph theory.

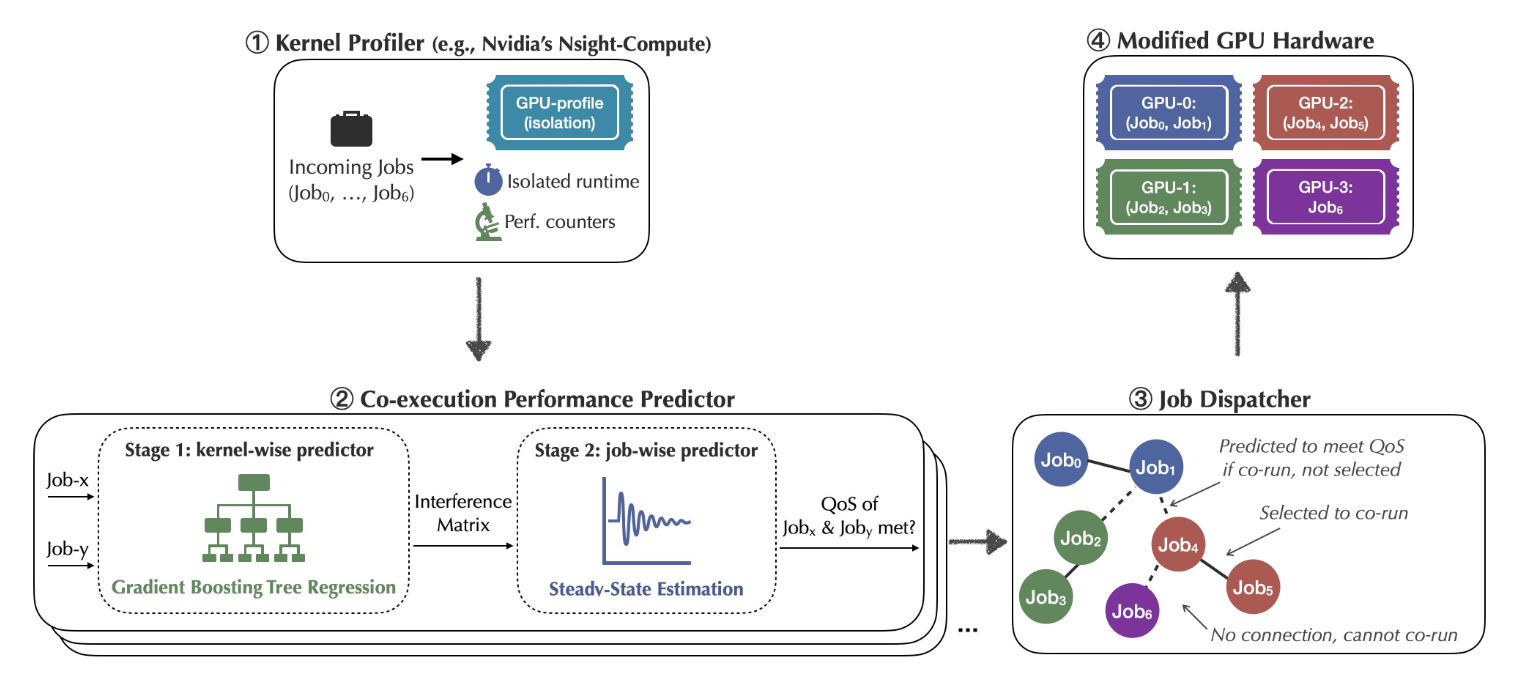

Based on these 2 observations, the author proposed GPUPool. Its overall system design is shown in Figure 2. It consists of 4 steps:

Kernel Profiler. GPUPool groups all incoming GPU job into a batch for every scheduling window (e.g., 30 seconds). User should provide application executable and execution time budget. Then GPUPool automatically profiles the application for one iteration of the job in isolation on hardware, to collect the performance counter metrics of each kernel of data.

Co-execution Performance Predictor. This step decides the compatibility of all possible job pairs within the batch using the profiling result. It contains 2 stages:

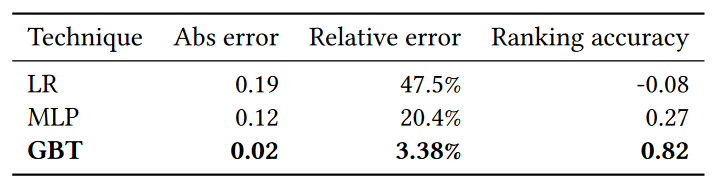

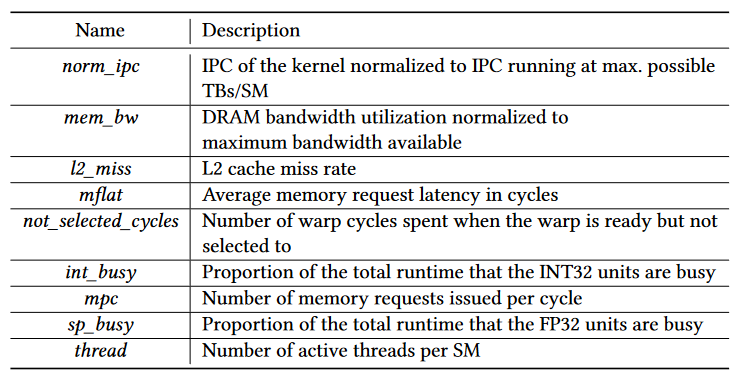

Kernel-wise Predictors. It predicts how well each kernel from one job will co-run with the ones in the other job. This stage uses a Gradient Boosting Tree (GBT) model to predict the performance of each kernel when co-running with another kernel (based on the 1st key observation). The model takes the profiling data of kernels as input and outputs the NP. This prediction will be done for each feasible TBs/SM settings.

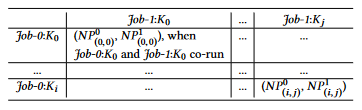

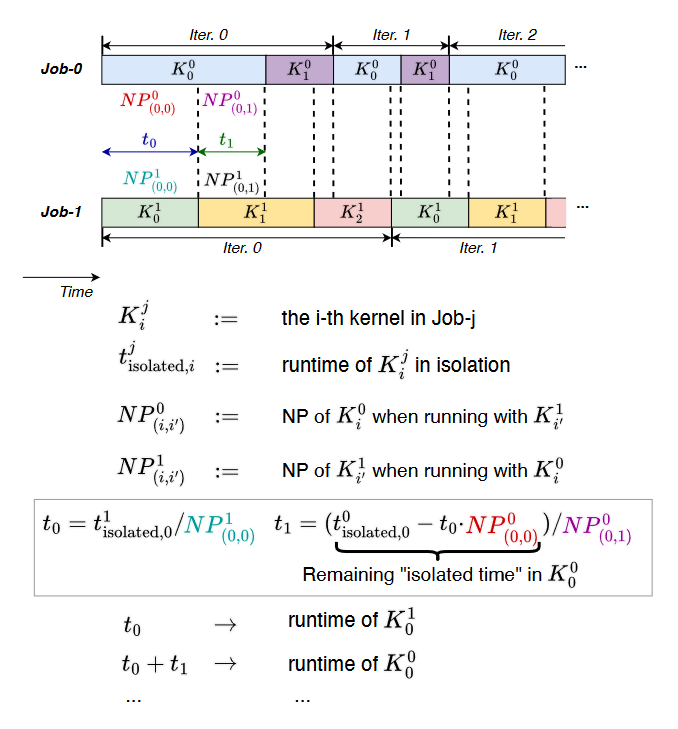

Job-wise Predictor. It gets an interference matrix (shown in Figure 3) based on the predicted NP (under optimal TBs/SM setting) from former stage, which indicates how will two kernels slow down when they are co-running. Then, GPUPool using this matrix to calculate the co-running time of two jobs. Here, the authors found that a whole calculation may require tens of thousands iterations, but the result will coverage to a steady-state after several iterations. So the authors used an approximation algorithm (shown in Figure 4) – stops timeline calculation once the accumulated slowdown values of each job is within a small delta over the past epoch.

- Job dispatcher. It decides which job pairs should co-run to maximize system performance while satisfying QoS. The decisions are found by solving a maximum cardinality matching problem – each node represent a job, when two jobs can co-run and will not violate the QoS requirement, connecting an edge between them. Then a graph theory algorithm is used to maximum cardinality matching, which means a largest subset of edges that do not share a common end node. Due to the potential unreliability of the performance predictor, GPUPool also add a safety margin $\delta$ to edge formulation.

$$E = \left{ ( {job} _ i, {job} _ j ) \mid {job} _ i,{job} _ j \in V\ \text{and}\ {NP} _ {job _ x} > {QoS} _ {job _ x} \times (1 + \delta ), x \in {i, j} \right}$$

- Execution. The batch of jobs are assigned to the modified GPU hardware.

Evaluations

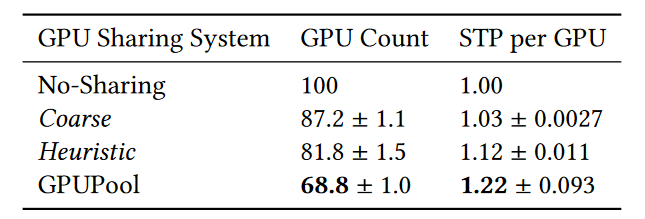

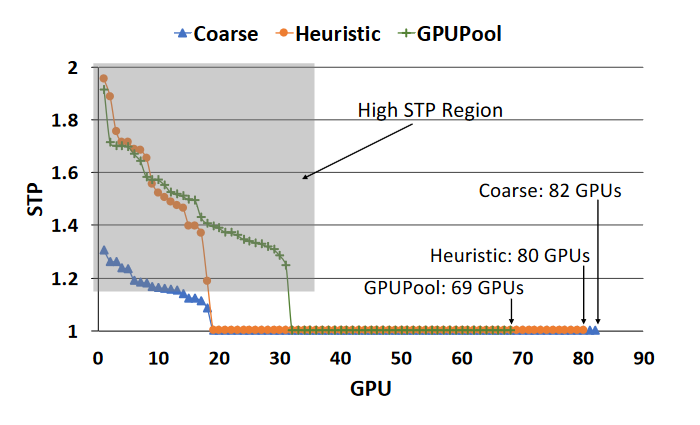

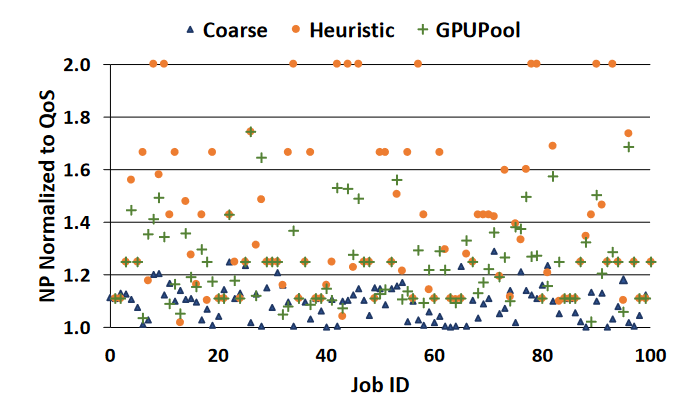

The paper compare GPUPool against three baseline systems:

No-Sharing.

Coarse: packing the jobs onto as few GPUs as possible using a greedy scheduling algorithm.

Heuristic: pairing up jobs with the highest and lowest bandwidth utilization (profiled offline) from a batch of incoming jobs.

The metrics is system throughput $STP=\sum_{i=1}^n \cfrac{t_{isolated}^i}{t_{shared}^i}$. $t_{isolated}^i$ and $t_{shared}^i$ are turnaround time of the i-th concurrent job when executing in an isolated and shared environment respectively. The paper also uses we use ${QoS}_{reached}$ to evaluate QoS fulfilment rate.

Comments

Strengths

This paper targets the fine-grained GPU sharing problem in the cloud. I believe this work provides a valuable solution to this problem.

From my perspective, fine-grained GPU sharing presents three key challenges:

Limitations imposed by hardware and CUDA, which make it difficult for programmers to flexibly control kernel execution.

Reliable and low-cost performance prediction for concurrent kernel execution. Establishing an analytical performance prediction model is highly challenging. One naive approach is using real hardware to profile, but due to the $\mathcal{O}(n^2)$ ($n$ representing the number of jobs) time complexity, this method is not scalable to larger clusters.

Efficient algorithms to find appropriate job combinations. If we allow an arbitrary number of jobs to execute concurrently, this becomes an NP-hard problem.

This paper cleverly addresses or bypasses these challenges through the following strategies:

Hardware-software co-design, which involves modifying hardware to provide more flexible API for upper-layer application. While this prevents the authors from testing their method on actual hardware and forces them perform experiments on simulator (GPGPU-Sim), I believe such simulations can provide valuable insights for adjustments on real hardware.

Predicting kernel concurrent execution performance by a ML model. This is a standout aspect of the paper (which is also my favorite novelty). The authors introducing ML with a good motivation to effectively addresses a challenging performance modeling problem, bypassing a complicated analytical modeling. Also, this ML model has good interpretability, top-10 import metrics (show in Figure) align well with human’s intuition. Furthermore, in my research experiences about Deep Learning Compiler (e.g., TVM), I also found many paper introduce such ML models for performance prediction. I believe the thought that leveraging ML techniques to bypass some complicated modeling problems is highly valuable in system research, which is the most important thing I learned from this paper.

Instead of solving the whole NP-hard job combination problem, the authors limit the number of concurrently executed jobs to 2, considering this simpler case. It is a fantastic tradeoff. The simplified problem can be solved by a maximum cardinality matching algorithm, which may not find the optimal combination, but exchanging reasonable scheduling overhead for a substantial performance improvement.

Weaknesses

This paper also has some potential weaknesses:

It seems to ignore the situation which two concurrent jobs have different execution times. For instance, when a longer job and a shorter job are executed together, after the shorter job finishes, GPUPool seems unable to schedule a new job to the GPU. Instead, the remaining GPU time is monopolized by the longer job. This could result in a lower resource utilization.

The concurrent execution of multiple jobs on a single GPU may also be constrained by GPU memory capacity. A possible improvement is to ask users to indicate maximum GPU memory usage of their applications and consider the these constraints when constructing the graphs.

This paper does not consider the job which leverages multiple GPUs. These jobs are quite common in reality. When a job can occupy multiple GPUs, there are some additional constraints:

Inter-GPU connection (e.g., NVLink or InfiniBand) bandwidth is the potential bottleneck, especially for distributed training strategies relying on high GPU interconnect bandwidth, such as Data Parallelism. Improper job scheduling may lead to contention for bandwidth among multiple jobs, or jobs requiring high GPU interconnect bandwidth may run on different nodes.

When a single job leverages multiple GPUs, the workload types on different GPUs may not be the same. For example, in Pipeline Parallelism, different GPUs run different stages of the neural network.

This paper does not clearly take into account the impact of memory hierarchy on performance, such as shared memory (or just implicitly consider it using a ML model). Some CUDA kernels are optimized by carefully utilizing CUDA SM shared memory, such as Flash Attention. When two kernels run together, does it lead to shared memory contention? Could it result in runtime errors or shared memory overflowing into global memory, causing a severe performance decline? Experiments in the paper can not answer these questions. Also, the selected profiling metrics to train stage 1 model listed in Figure 5 do not contains any metrics about shared memory capacity. Another possibility is that a ML model is already good enough to handle this problem. Regardless, the impact of memory hierarchy on GPU-sharing deserves further study.

Possible Improvements

I have some potential ideas to improve this work:

As response to the first weakness mentioned above, we can extend GPUPool to enable it to schedule a new job to the GPU after the shorter job finishes. This improvement can be achieved by a simple modification: keep the running jobs in the incoming window, and if two jobs are still running in the same GPU, also keep the edge between them in the pairing graph. With this modification, if shorter job finishes, we can re-run the matching algorithm to find a new job to pair with it.

We can extend GPUPool to support multiple GPU job. To achieve that, we should consider inter-GPU connection bandwidth. This may include following modifications:

Ask users to indicate the required inter-GPU bandwidth or connection types (e.g., NVLink/PCIe/Infiniband/Ethernet).

Take a multiple GPU task as several sub-jobs. Each of sub-job is a single GPU job, with interconnection constraints. Then we can reuse the infrastructure of GPUPool to find the co-running chances.

Extend the last step “Execution” to consider the interconnection constraints, so it can dispatch sub-jobs to nodes that meet the constraints. This may require an efficient graph algorithm to find job placement, which requires a further research.

Sometimes the goal of a data center is not just to improve resource utilization, but also to save energy. Improving resource utilization does not necessarily mean energy saving, because the chip’s speed $S$, power consumption $P$, and frequency $f$ have the following approximate relationship:

$$\begin{align}

S & \propto f \

P & \propto f^\alpha, \text{while}\ \alpha \in [2, 3]

\end{align}$$

We can extend the optimization target of GPUPool to power consumption. This can be achieved by add a power prediction model with similar methods. Then we can use a multi-objective optimization algorithm to find the best job combination, considering both performance and power consumption.