[Paper Reading] ACS: Concurrent Kernel Execution on Irregular, Input-Dependent Computational Graphs (arXiv'24)

This blog is a write-up of the paper “ACS: Concurrent Kernel Execution on Irregular, Input-Dependent Computational Graphs“ from arXiv’24.

Motivation

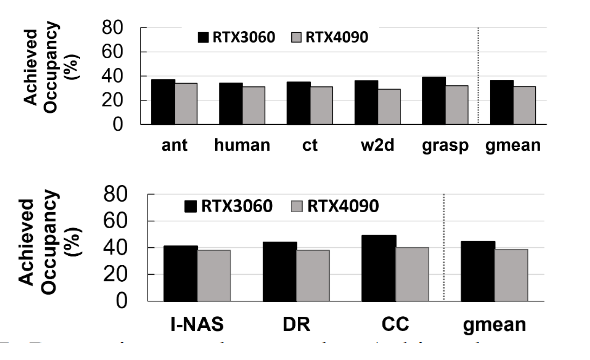

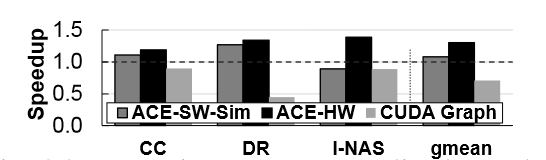

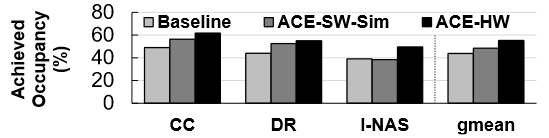

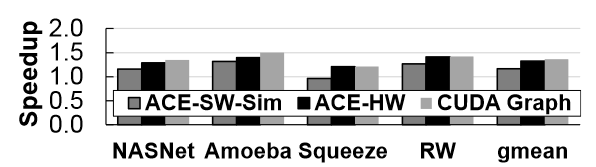

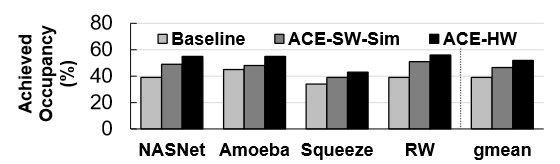

Some workloads (e.g., Simulation Engines for Deep RL, Dynamic DNNs) cannot fully utilize the massive parallelism of GPUs (see Figure 1). The main reason is that these workloads contain lots of small kernels which cannot fully utilize the GPU, and these kernels are not executed concurrently, although most of them are independent and in theory can be executed concurrently.

But there are some challenges to execute these kernels concurrently:

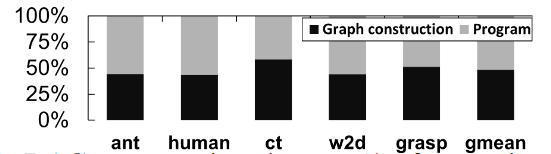

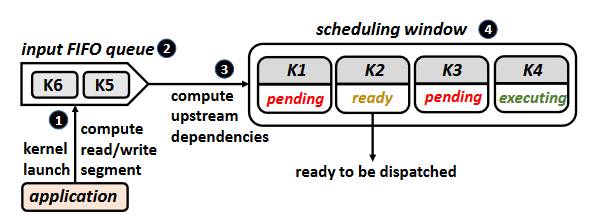

- Input-dependent kernel dependencies. For some workload, the the dependencies between kernels are only determined at runtime for each input. Constructing full computational graph and resolving dependencies before execution will introduce high latency (see Figure 2,average of 47% of overall execution time as the paper says).

- Irregular kernel dependencies. Some workloads have irregular computational graphs. We can partitioned the computational graph of the workload into independent streams of kernels. But this would require fine-grained scheduling and synchronization, with large overhead (see Figure 3).

Existed solutions:

CUDA Graph and AMD ATMI. They allow users specify dependencies between different kernels as DAG, and can eliminate the synchronization and kernel launch overhead. But the DAG needs to be constructed in full before execution, which imakes them not suitable for dynamic kernel dependencies (such as Dynamic DNNs).

Using events provided by the CUDA stream management API, which allows synchronization between kernels across streams through the

cudaStreamWaitEventAPI, without blocking the host. But approach still requires deriving dependencies between all kernels beforehand.Persistent threads (PT) can eliminate the scheduling and launch overheads, but are only effective when all kernels are homogeneous.

PT is just like coroutine in some programming languages.

CUDA dynamic parallelism (CDP) or AMD’s device enqueue (DE) enables parent kernels to launch child kernels, but , only allowing data dependencies between one parent and its children (so cannot be use to synchronize between multiple tasks).

Design

The goal of this paper is to design a framework that enables efficient concurrent execution of GPU kernels with:

lightweight detection of inter-kernel dependencies at runtime,

low overhead kernel scheduling and synchronization.

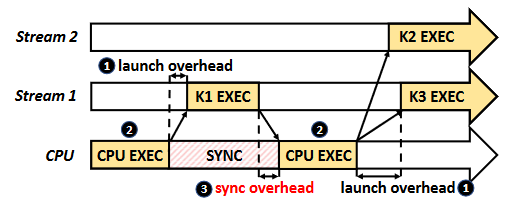

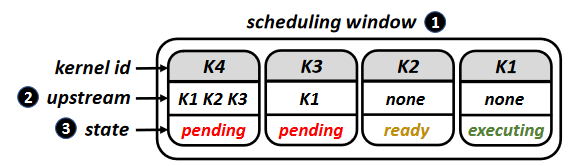

The key idea is to perform the dependence checking and scheduling within a small window of kernels at runtime similar to out-of-order instruction scheduling.

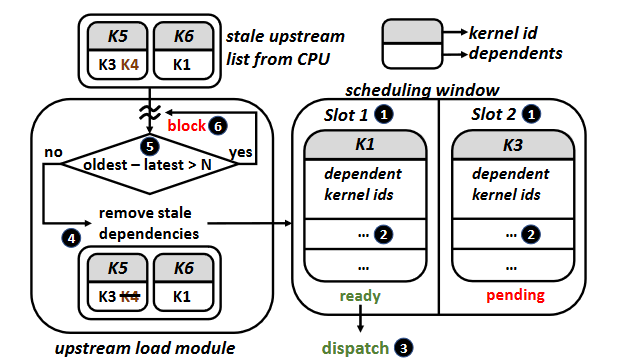

The authors proposed Automatic Concurrent Scheduling (ACS) as solution. The overall design of ACS-SW is shown in Figure 4. It contains three main functionalities:

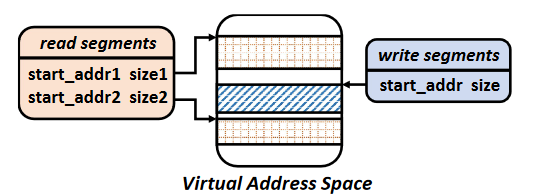

Determining inter-kernel dependencies. By checking for overlaps between read segments and write segments, we determine dependencies between kernels. For a wide range of commonly used kernels (e.g., matrix multiplication, convolution), we can infer the read and write segments from the input easily. But for some kernels, it’s impossible to determine the range of memory accessed statically because of the potential indirect memory accesses, so the authors just assume the entire GPU memory may be accessed.

The authors use a kernel wrapper to finish the dependency detection.

get_addresses()is called to get__read_segments__and__write_segments__.1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13struct ACE_wrapper {

//list of read,write segments defined as

//[{start_adr1,size1},{start_adr2,size2}..]

list __read_segments__;

list __write_segments__;

// function which gets called at kernel

// launch to populate read,write segments

void get_addresses(

dim3 blocks, dim3 threads, ...

);

// function declaration of the kernel

static __global__ void kernel(...);

};Tracking kernel state at runtime. The kernels in the window can be three states:

- Ready: kernels it is dependent on complete execution.

- Pending: upstream kernels are still pending or executing.

- Executing.

- Eliminating CPU synchronization overheads. See ACS-HW for more details.

ACS has two variants:

ACS-SW: software-only implementation which emulates the out-of-order kernel scheduling mechanism.

ACS-HW: hardware-facilitated implementation which is more efficient as it also alleviates synchronization overheads.

ACS-SW

Window Module

This module is to determining inter-kernel dependencies. It is implemented as a separate thread that manages the input FIFO queue and the scheduling window. The kernel state tracking is implemented in the hardware.

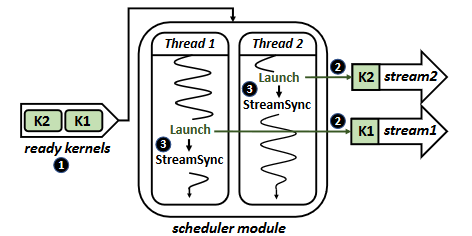

Scheduler Module

This module schedules and launches ready kernels for execution. It has fixed number of CUDA streams. Each stream contains only one kernel at any given time. Threads with empty streams poll the scheduling window for a ready kernel.

ACS-HW

ACS-SW incurs kernel synchronization and launch overheads because scheduler module launches a kernel in the CPU. ACS-HW solves these problems by a software-hardware co-design.

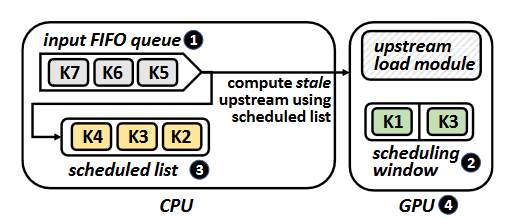

Software-side: maintains an input FIFO queue like ACS-SW, and a list of kernels in the GPU’s scheduling window, but it can be stale.

Hardware-side: the scheduling window and its management are implemented in hardware on the GPU side.

A key novelty in hardware design is two stage dependency detections. First, ACS use software to perform initial detection using stale kernel information (without frequent synchronize overhead), then utilizes hardware to correct outdated dependency information. This two-stage approach significantly reduces the hardware complexity.

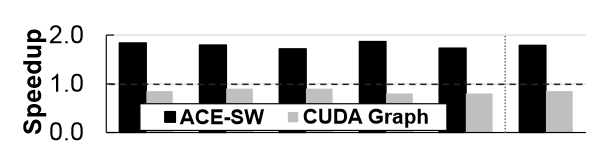

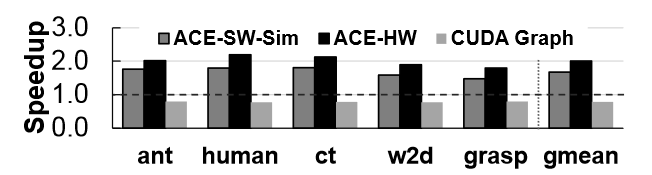

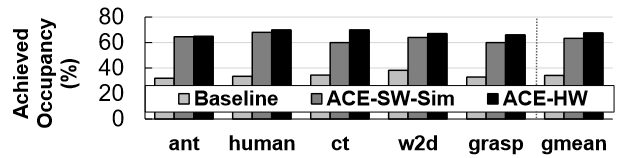

Evaluation

- Baseline: cuDNN implementation (for DNNs) and a jax implementation (for deep RL simulation), both using CUDA streams.

- ACS-SW: on real hardware.

- ACS-SW-Sim: ACS-SW on the GPU simulator.

- ACS-HW: on the GPU simulator.

- CUDAGraph.

Comments

Strengths

This paper focuses on the problem of low GPU utilization caused by the serial execution of numerous small CUDA kernels. I believe this paper effectively addresses this problem, particularly with the following innovative points that are impressive me:

Out-of-order dependency detection and scheduling. Out-of-order (OoO) is a common technique in micro-architecture and software (e.g., hard disk I/O queue) designs. It’s an impressive and innovative idea to introduce OoO into this area to find the dynamic dependencies efficiently.

A good trade-off. When I first read the Introduction section of the paper, I thought the read-write dependencies detection may be a difficulty task. To my knowledge, there aren’t reliable static binary memory access analysis techniques (otherwise, segmentation fault wouldn’t be a common problem). However, the authors made a good simplification and trade-off regarding this problem. For most common kernels, memory access areas can be inferred from input parameters. For the rest kernels, it can be assumed that they access the entire memory. Since few common operators occupy most of the execution time, this trade-off leads to significant performance improvements with a relatively low scheduling overhead. This innovation is my favorite aspect of this paper.

Two-stage dependency detection in ACS-HW. While a complete hardware dependency detection approach is theoretically feasible, it could incur significant chip area costs (as we know, the re-order buffer in microprocessor carries large area). The authors proposed a two-stage software-hardware co-design dependency detection, significantly simplifying the difficulty of hardware design. It is a brilliant idea.

Weaknesses

This paper has some potential weaknesses:

To each type of kernel, we must custom

get_addressesfunction int the kernel wrapper. This weakness may limit the adoption of ACS.Deciding whether kernels should be executed concurrently requires considering more factors than just data dependencies. If there are resource conflict (e.g., memory bandwidth, shared memory size) between two large kernels, performance may degrade if they co-execute.

Improvements

I propose some potential improvements to this paper:

In response to the first weakness mentioned above, I propose a profiling-rollback strategy to achieve safe automatic dependency detection. This strategy leverages the commonly used paging technique in OS virtual memory management: we can set a memory page as read-only or write-only. When a program is running, if a page fault is triggered, we can know that a read/write occurs. While I’m unsure if Nvidia GPUs provide APIs for user to control page tables, let’s assume such APIs exist. Given that many workloads are iterative (e.g., neural network training), we can profile the workload just one iteration, utilizing the aforementioned paging trick to record the memory access segments of each kernel. Obviously this may introduce some inaccuracies, we need a rollback strategy to ensure correct program execution. During runtime, we set known

__write_segments__as read-write, while other areas are set as read-only. Upon encountering a page fault, we detect an error and revert to the default strategy (assuming all memory areas will be read and wrote). With this strategy, we can eliminate the need of manualget_addressesfunction, and maximize the potential parallelism.Regarding the second weakness, I suggest adopting the method of GPUPool to determine which kernels are suitable for concurrent execution. A naive solution involves tracking the number of SMs each kernel occupies. When the SMs of a GPU are fully occupied, even if there are kernels in the

readystate and available CUDA streams, no new kernels are scheduled.