How Quantization Works: From a Matrix Multiplication Perspective

Introduction

Quantization is a commonly used acceleration technique in NN inference. The primary computational workloads in NNs come from Convolution, Linear Layers, and Attention, which are implemented by GEMM in the lower level. This blog aims to discuss the principles of quantization from the matrix multiplication perspective and to explain why some quantization methods are impractical. It also aims to review several LLM quantization methods from this perspective.

I define practical quantization as follows:

- Operation can still be performed using GEMM after quantization. This requires both mathematical feasibility and hardware support. It is a fundamental requirement for achieving acceleration.

- Quantization must lead to actual acceleration. Acceleration can arise from higher INT8 hardware throughput, or from the memory bandwidth saved by smaller memory footprint. Importantly, the benefits of acceleration must outweigh the quantization overhead.

Let’s do some math

Suppose an operator can be expressed in the form of matrix multiplication:

$$\mathbf{Y}=\mathbf{X} \mathbf{W}^\top,$$

where $\mathbf{X} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times C}$, $\mathbf{Y} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times D}$, $\mathbf{W} \in \mathbb{R}^{D \times C}$, while their quantized versions are denoted as $\hat{\mathbf{X}}$, $\hat{\mathbf{Y}}$, $\hat{\mathbf{W}}$. Our goal is to ensure that operations can still be performed using GEMM after quantization, i.e.:

$$\hat{\mathbf{Y}}=\hat{\mathbf{X}} \hat{\mathbf{W}}^\top.$$

Let the per-element quantization functions for $\mathbf{X}$, $\mathbf{Y}$, and $\mathbf{W}$ be denoted as $p_{nc}(\cdot)$, $q_{nd}(\cdot)$, $r_{dc}(\cdot)$ respectively:

$$\begin{aligned}

\hat{x}_ {nc} &= p_ {nc}(x_{nc}), \\

\hat{y}_ {nd} &= q_ {nd}(y_{nd}), \\

\hat{w}_ {dc} &= r_ {dc}(w_{dc}).

\end{aligned}$$

The corresponding dequantization functions are denoted as $p_ {nc}^{-1}(\cdot)$, $q_ {nd}^{-1}(\cdot)$, $r_ {dc}^{-1}(\cdot)$, i.e.:

$$\begin{aligned}

y_ {nd}

&= \sum_ {c=1}^{C} x_ {nc} w_ {dc}, \\

q_ {nd}^{-1}(\hat{y}_ {nd}) &= \sum_ {c=1}^{C} p_ {nc}^{-1}(\hat{x}_ {nc}) \cdot r_ {dc}^{-1}(\hat{w}_ {dc}).

\end{aligned}$$

The above formulas set the basic constraints that practical quantization should satisfy mathematically.

Some basic quantization methods

With this basic constraints, we can now discuss several fundamental quantization methods, including per-element, per-channel, per-token, and per-tensor quantization.

Per-element and Per-channel

In the basic constraints mentioned above, the dequantization function $q_ {nd}^{-1}(\cdot)$ on the left-hand side does not depend on $c$. Clearly, if the right-hand side quantization functions $p_ {nc}^{-1}(\cdot)$ and $r_ {dc}^{-1}(\cdot)$ depend on $c$, this constraint will be violated. This implies that these two conditions cannot be satisfied at the same time:

- Computation can be done by GEMM.

- Different quantization functions can be applied in different channels of $\mathbf{X}$ and $\mathbf{W}$.

In other words, this indicates that per-element and per-channel quantization cannot be accelerated using GEMM. They are impractical.

Per-token and per-tensor

From the above discussion, we know that practical quantization needs to satisfy at least:

$$\begin{aligned}

p_ {n}(\cdot) &= p_ {nc} (\cdot), \quad \forall n, c, \\

r_ {d}(\cdot) &= r_ {dc} (\cdot), \quad \forall d, c.

\end{aligned}$$

That is, the quantization function is same for all channels. Therefore, the basic constraint can be formulated as:

$$q_ {nd}^{-1}(\hat{y}_ {nd}) = \sum_ {c=1}^{C_ i} p_ {n}^{-1}(\hat{x}_ {nc}) \cdot r_ {d}^{-1}(\hat{w}_ {dc}),$$

Thus, we get per-channel quantization. If we further assume:

$$\begin{aligned}

p(\cdot) &= p_ {nc} (\cdot), \quad \forall n, c, \\

r(\cdot) &= r_ {dc} (\cdot), \quad \forall d, c.

\end{aligned}$$

That is, the quantization function is same for all elements in both $\mathbf{X}$ and $\mathbf{W}$. Therefore, the basic constraint can be formulated as:

$$q_ {nd}^{-1}(\hat{y}_ {nd}) = q^{-1}(\hat{y}_ {nd}) = \sum_ {c=1}^{C_i} p^{-1}(\hat{x}_ {nc}) \cdot r^{-1}(\hat{w}_ {dc}).$$

We thus obtain per-tensor quantization. While both of these quantization methods have theoretical feasibility, the practical values of them are still limited by hardware support (as discussed in the next section).

For convenience, the following discussion focuses only on per-token quantization. Per-tensor quantization can be seen as a special case of per-token quantization. The most commonly used quantization method in practice is symmetric uniform quantization, which scales the value range using multiplication, i.e.:

$$\begin{aligned}

\hat{x}_ {nc} &= p_ {n}(x_ {nc}) = p_ n x_ {nc}, \\

\hat{w}_ {nd} &= r_ {d}(w_ {dc}) = r_ d w_ {dc}, \\

\hat{y}_ {dc} &= q_ {nd}(y_ {nd}) = p_ n r_ d y_ {nd}.

\end{aligned}$$

We can formulate per-token symmetric uniform quantization by matrix multiplication:

$$\begin{aligned}

\hat{\mathbf{X}} &= \text{diag}(p_1,\cdots,p_ N)\cdot \mathbf{X} = \begin{pmatrix}

p_ 1 & \cdots & p_ 1 \\

\vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\

p_ N & \cdots & p_ N

\end{pmatrix} \otimes \mathbf{X}, \\

\hat{\mathbf{W}} &= \text{diag}(r_1,\cdots,r_ D)\cdot \mathbf{W} = \begin{pmatrix}

r_ 1 & \cdots & r_ D \\

\vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\

r_ 1 & \cdots & r_ D

\end{pmatrix} \otimes \mathbf{W}, \\

\hat{\mathbf{Y}} &= \text{diag}(p_1,\cdots,p_ N)\cdot \mathbf{Y} \cdot \text{diag}(r_1,\cdots,r_ D) = \begin{pmatrix}

p_ 1 r_ 1 & \cdots & p_ 1 r_ D \\

\vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\

p_ N r_ 1 & \cdots & p_ N r_ D

\end{pmatrix} \otimes \mathbf{Y},

\end{aligned}$$

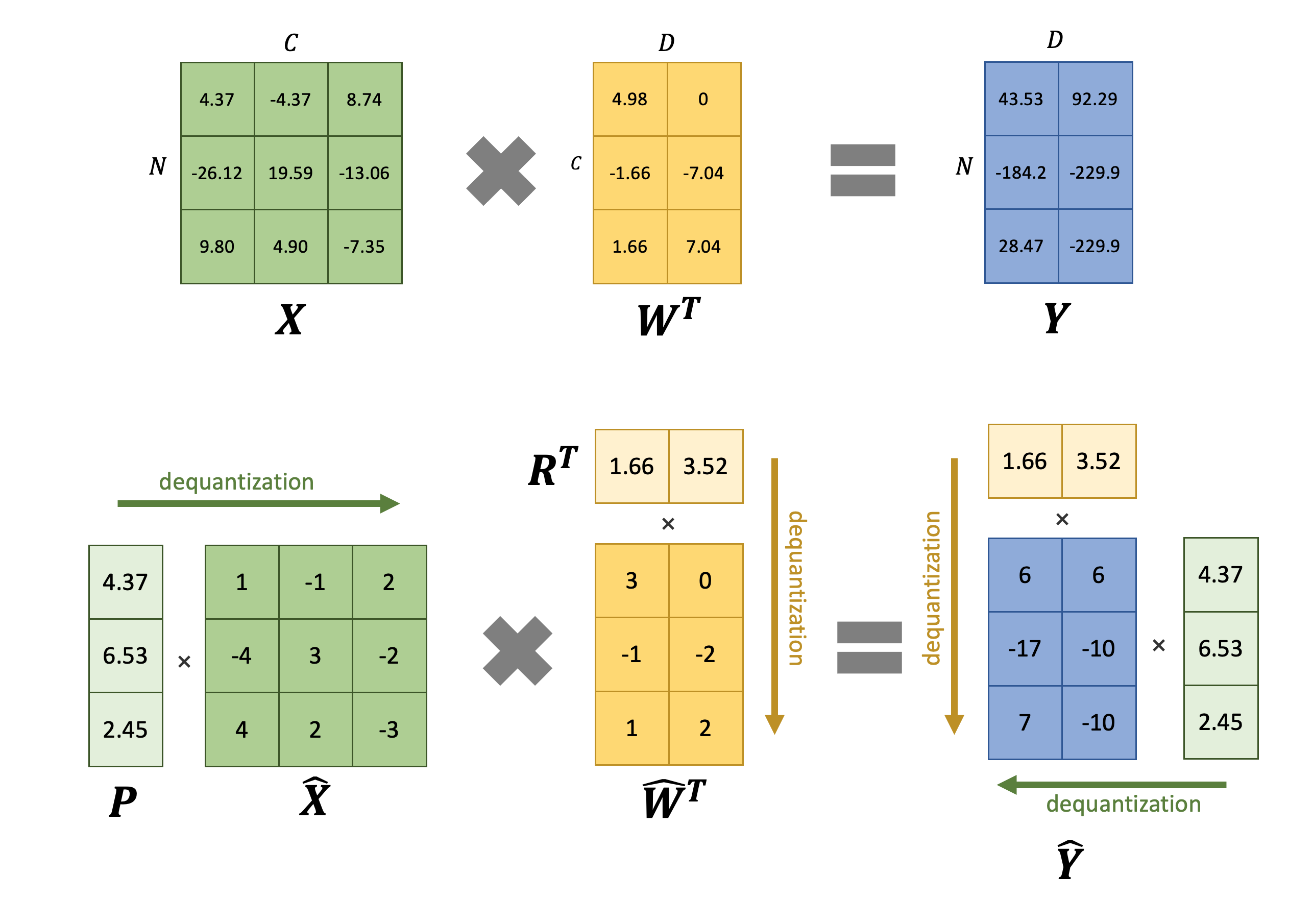

where $\otimes$ represents element-wise matrix multiplication. It can be observed that both quantization and dequantization can be efficiently implemented using element-wise matrix multiplication with dimension broadcasting. The following figure illustrates the computation process by an example:

Hardware requirements

Hardware support still need to be considered when we try to utilize GEMM for quantization. For example, on NVIDIA GPUs, Tensor Core supports matrix multiplication for FP16 and INT8, but it doesn’t support mixed precision matrix multiplication for FP16/INT8. This means that W8A8 quantization can benefit from Tensor Core, but W8A16 and W16A8 quantization lack hardware support and may not achieve real acceleration on NVIDIA GPUs. Many W8A16 and W16A8 quantization methods actually perform dequantization before GEMM and then use FP16 for computation. The actual acceleration effects of these methods require further discussion (see below).

Performance analysis

The above discussion only shows that per-token quantization can leverage GEMM. The following words will show whether it can provide actual acceleration.

We compare the following three setups:

- Unquantized, using FP16 for both storage and computation.

- W8A8 quantization, with I/O activations stored in FP16. This is the approach used by some works like

LLM.int8(). To avoid additional CUDA kernel launch overhead, we assume that quantization and dequantization are fused with GEMM. - W8A16 quantization, internally converting weights to FP16 for computation. Kernel fusion is also applied here.

Without loss of generality, we can assume that the hardware INT8 throughput is $2\times$ than that of FP16. We can set normalized operations of one INT8 operation is $1$, while $2$ for FP16. We can list the following table:

| Method | FP16 | W8A8 (FP16 activations I/O) | W8A16 |

|---|---|---|---|

| GEMM OPs | $2NCD$ | $NCD$ | $2NCD$ |

| GEMM mem I/O | $2(NC+CD+ND)$ | $2NC+CD+2N D$ | $2NC+CD+2ND$ |

| quant/dequant OPs | $0$ | $2NC+4ND$ | $2CD$ |

| quant/dequant Mem I/O | $0$ | $2(N+C_o)$ | $2D$ |

| total OPs | $2NC D$ | $NC D+2NC+4N D$ | $2NCD+2CD$ |

| total mem I/O | $2(NC+C D+N D)$ | $2NC+C D+2N D+2(N+C_o)$ | $2NC+CD+2ND+2D$ |

| total arithmetic intensity (OPs:I/O) | $\cfrac{1}{1/N+1/C+1/D}$ | $\cfrac{1+2/D+4/C}{2/N+1/C+2/D+2/(NC)+2/(CD)}$ | $\cfrac{1+2/N}{1/(2N)+1/C+1/D+1/(NC)}$ |

| total arithmetic intensity (second-order approximation) | $\cfrac{1}{1/N+1/C+1/D}$ | $\cfrac{1}{2/N+1/C+2/D}$ | $\cfrac{1}{1/(2N)+1/C+1/D}$ |

Analyzing the table above, we can draw the following conclusions:

- W8A8 quantization (with FP16 activations I/O) reduces the operations by almost half compared to FP16, but it decreases the total arithmetic intensity. Therefore, in memory-bound scenarios, W8A8 quantization may not achieve a $2\times$ throughput improvement (ZeroQuant addresses this issue, as discussed below). But it can still lead to a significant throughput improvement when memory bandwidth is sufficient.

- W8A16 quantization maintains a similar operations compared to FP16, but it slightly increases the total arithmetic intensity (more increase when $N$ is large). Therefore, it also has practical value in memory-bound scenarios, especially since activations in LLMs are typically harder to be quantized than weights.

Some LLM Quantization works

LLM.int8()

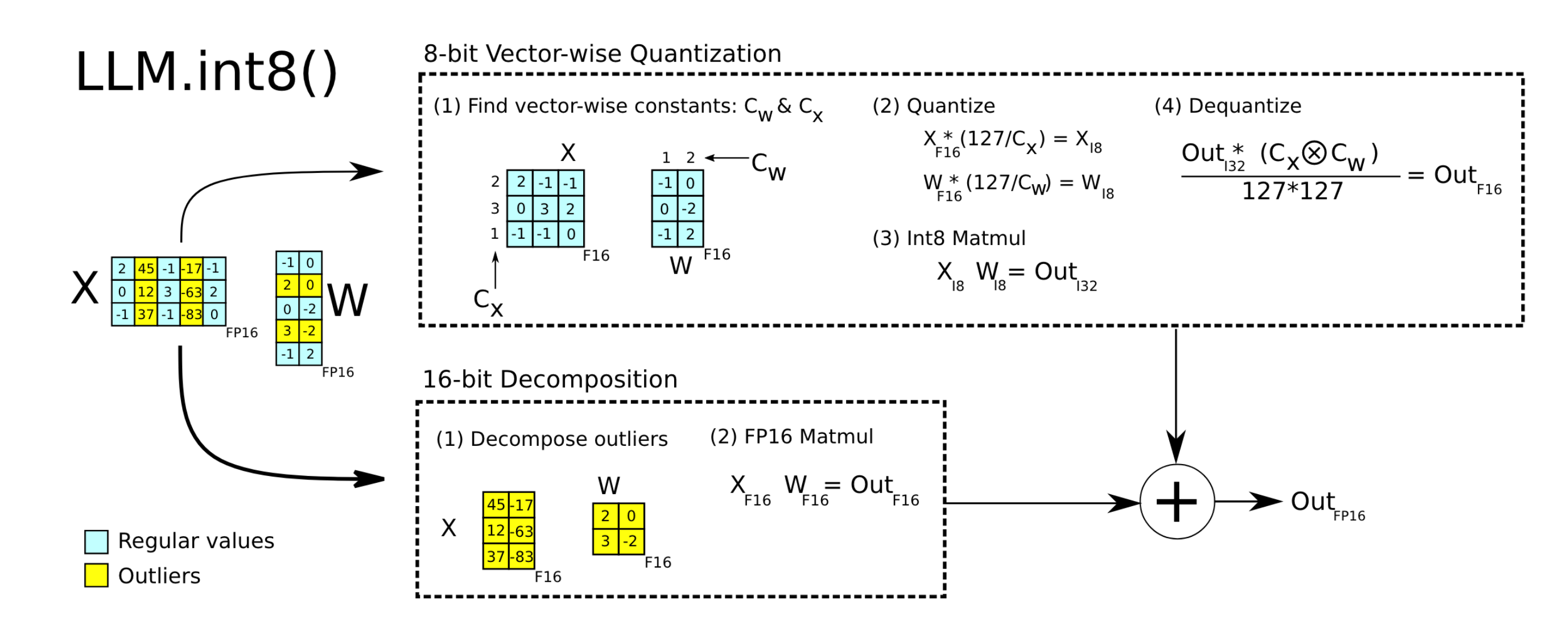

LLM.int8() actually employs selective per-token quantization. It stores weights and activations in FP16 and then applies different strategies for different tokens, as illustrated below:

- For tokens suitable for quantization, it applies per-token INT8 quantization to weights and activations, computes results using INT8 GEMM, and then dequantizes them to FP16.

- For tokens with outliers, it directly computed the FP16 GEMM.

The results from these two parts can be combined to form the final result.

SmoothQuant

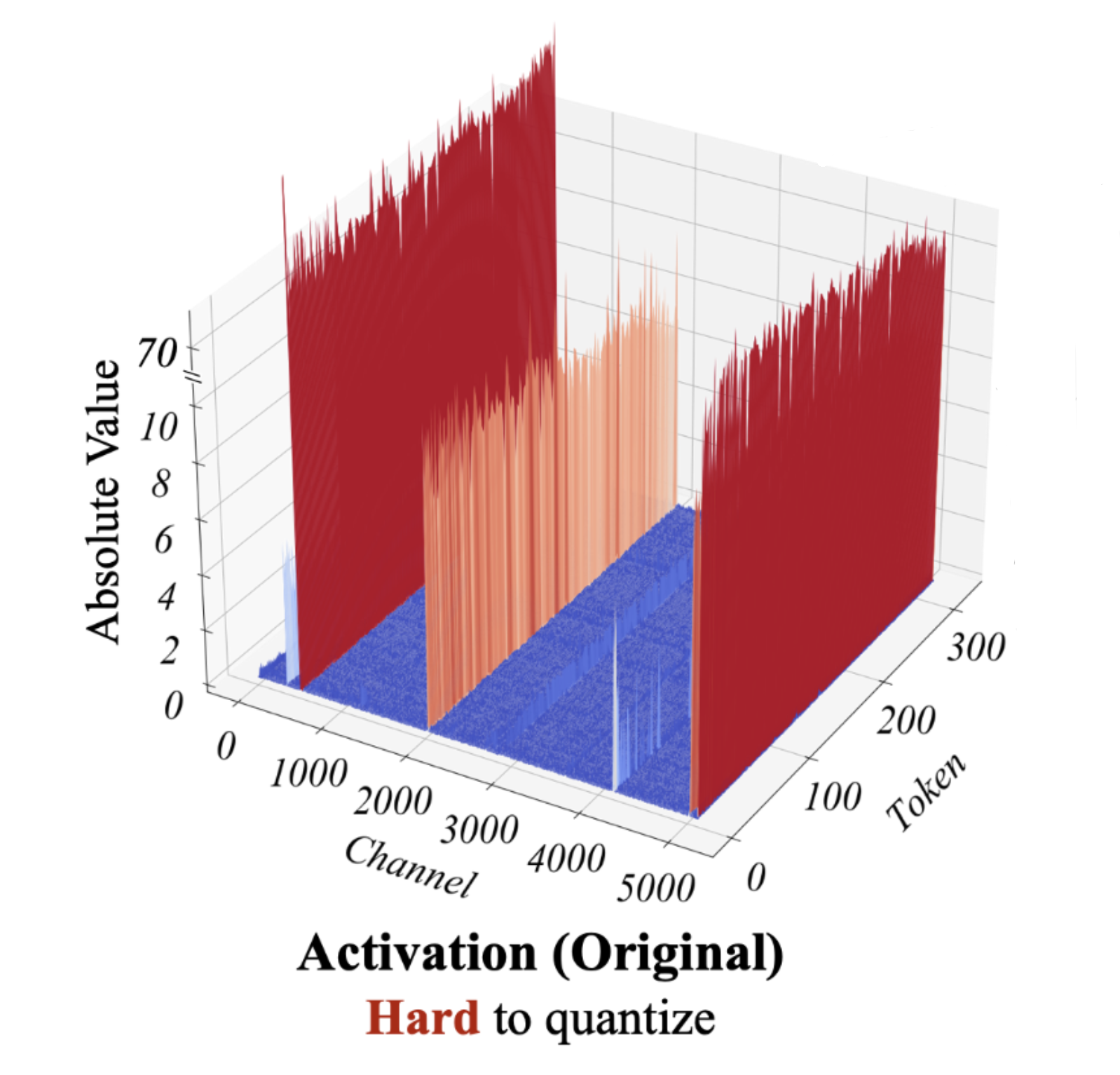

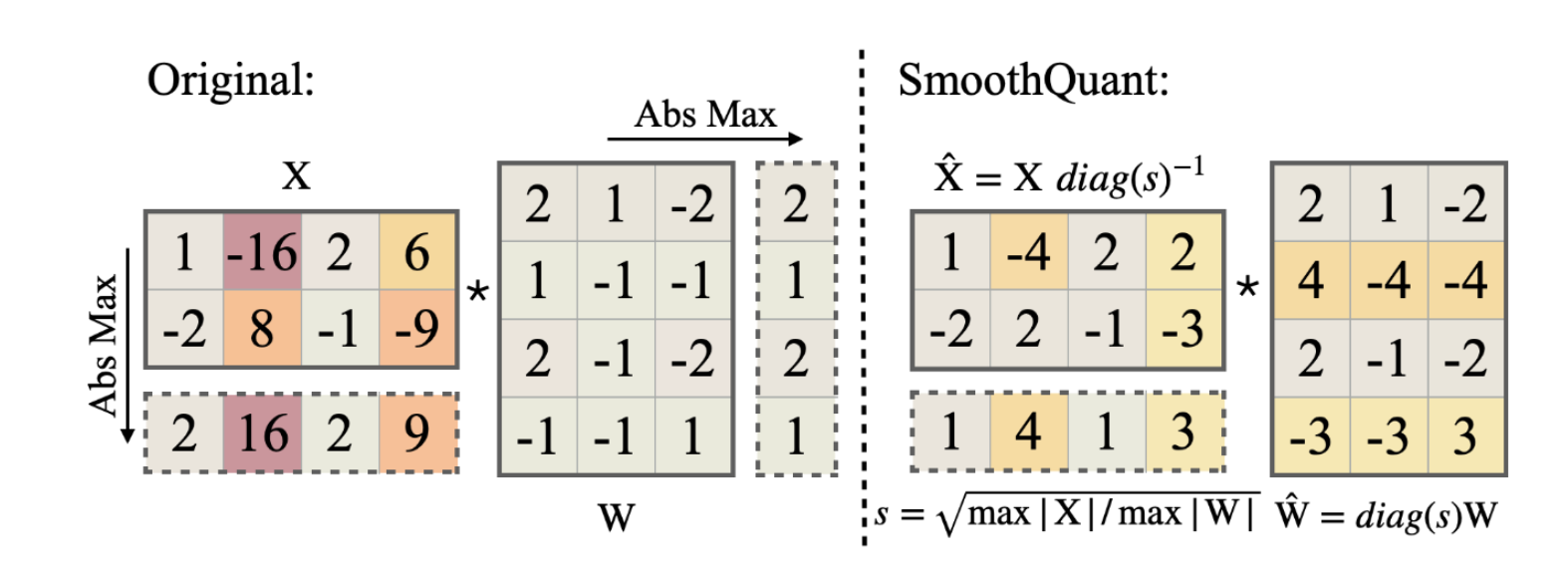

While per-channel quantization may not be practical, for LLM activation quantization, the main challenge arises from activations, where values with larger magnitudes may appear on some channels, as shown below:

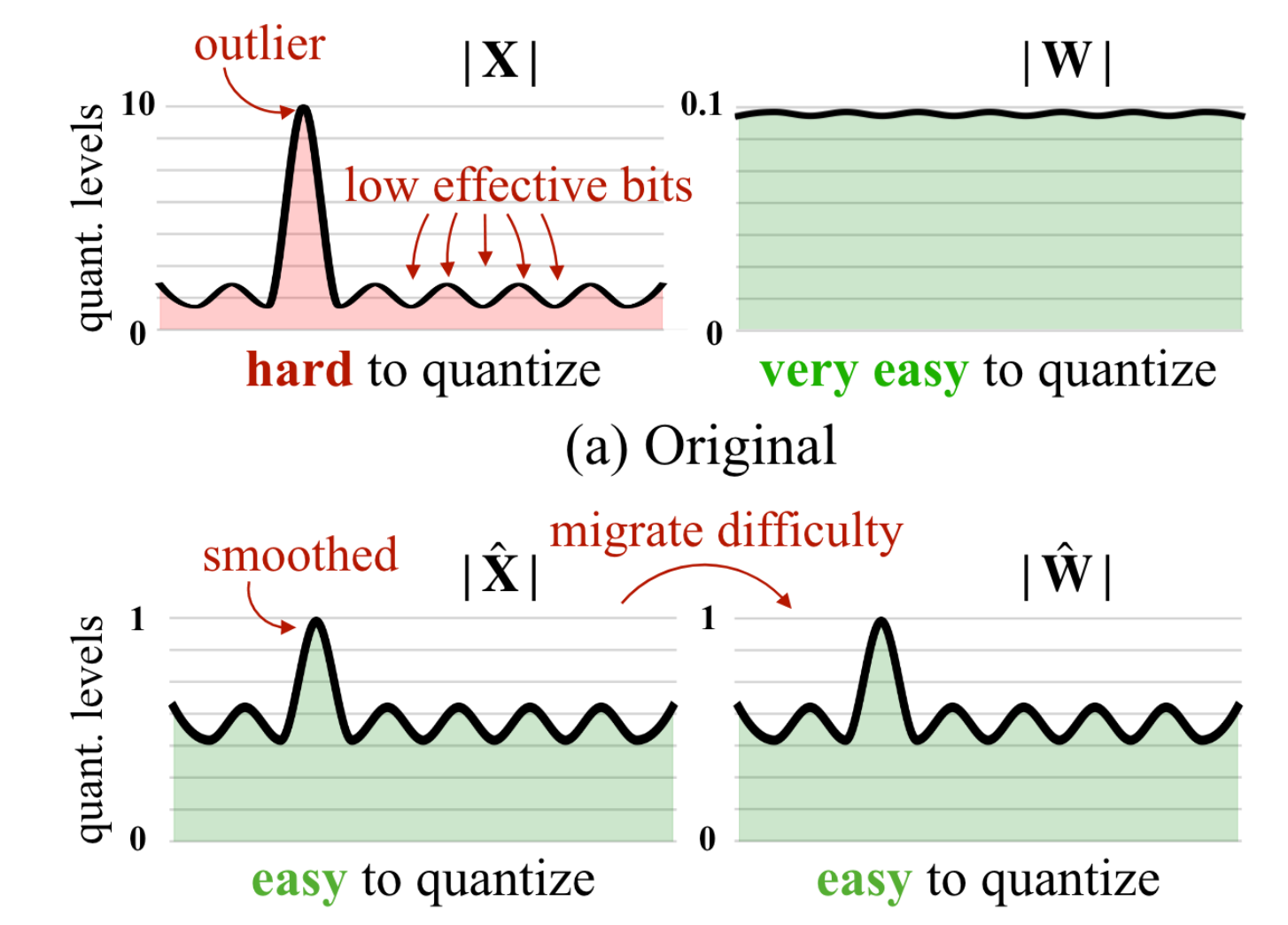

SmoothQuant observed that these outliers occur consistently in specific channels, while outliers are rare in weights (thus easier to quantize). Therefore, it proposes to “balance” the quantization difficulty between activations and weights by introducing a per-channel scaling factor:

This “balance” can be formulated as:

$$\begin{aligned}

\mathbf{Y}

&= \mathbf{X}\mathbf{W}^\top \\

&= \mathbf{X} \cdot \text{diag}(s_ 1,\cdots,s_ C) \cdot \text{diag}(s_ 1,\cdots,s_ C)^{-1} \cdot \mathbf{W}^\top \\

& = \left( \mathbf{X} \cdot \text{diag}(s_ 1,\cdots,s_ C) \right) \cdot \left( \mathbf{W}\cdot \text{diag}(s_ 1,\cdots,s_ C)^{-1} \right)^\top.

\end{aligned}$$

By selecting appropriate scaling factors $\text{diag}(s_ 1,\cdots,s_ C)$, we can achieve the goal of balancing outlier values in activations, and then we can quantize $\mathbf{X} \cdot \text{diag}(s_ 1,\cdots,s_ C)$ and $\mathbf{W}\cdot \text{diag}(s_ 1,\cdots,s_ C)^{-1}$. The following figure give an example:

SmoothQuant is an excellent alternative to per-channel quantization, as demonstrated in the paper by its impressive performance in quantizing LLM to W8A8.

ZeroQuant

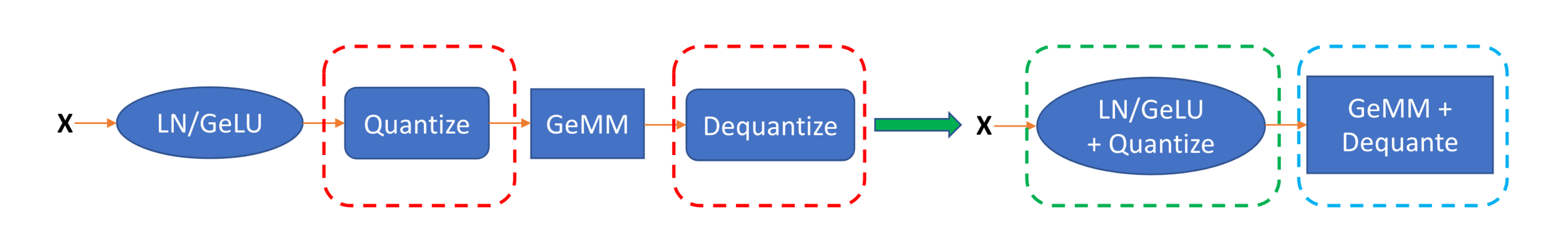

In the above performance analysis of W8A8, we found that using FP16 for activations I/O reduces the overall arithmetic intensity after quantization, which may harm the throughput improvement in memory-bound scenarios. ZeroQuant addresses this issue by fusing the quantization into the previous operator and fusing the dequantization after GEMM, as shown in the figure below.

Thus, the activations I/O between operators are still INT8, which reduces the total memory I/O to $NC+CD+ND+2(N+D)$, boosting arithmetic intensity to original FP16 level , and fully leveraging the high throughput of INT8.

Conclusion

This blog provides a matrix multiplication perspective for quantization, indicating some fundamental requirements for practical quantization and explaining why per-channel quantization in impractical. It also discusses several examples of LLM per-token quantization, including LLM.int8(), SmoothQuant, and ZeroQuant.

They are all practical and demonstrate significant acceleration in real-world scenarios.